75 years ago – Bomber Command raid on Leipzig

Header image: Lancasters outbound at dusk.

75 years ago this month, on the night of 19/20th February 1944, RAF Bomber Command launched a major bombing raid against the German city of Leipzig at the beginning of the so-called ‘Big Week’. It was to prove to be the most costly, in terms of losses for the RAF, of the war so far. Leipzig was attacked in an attempt to destroy four Messerschmitt aircraft factories where Bf109 fighters were built, and a ball-bearing plant located in the city.

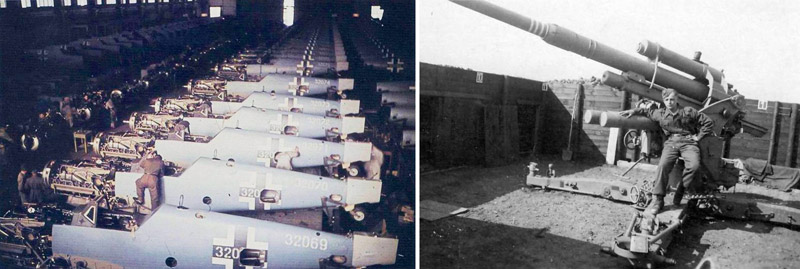

Right: A German anti-aircraft gunner with his 88mm ‘flak’ gun in Leipzig. Note the three kill markings on the barrel.

A total of 823 RAF bombers were sent out to attack Leipzig: 561 Lancasters, 255 Halifaxes and seven Mosquitos. The German fighter controllers did not take the bait of the diversionary minelaying raid to Kiel or the 15 Mosquitos that mounted a diversionary raid on Berlin. They marshalled their forces well; the bomber stream was under constant attack by night fighters from the Dutch coast all the way to the target and back, and also experienced heavy ‘flak’. There were further difficulties at the target because the winds were not as forecast and many aircraft reached the Leipzig area too early and had to orbit to await the Pathfinders. Four bombers were lost by collision and approximately 20 were shot down by ‘flak’. Leipzig was cloud-covered and the Pathfinders had to use sky marking. The bombing appeared to be concentrated in its early stages but became scattered later.

Of the 823 RAF aircraft sent to Leipzig, 78 failed to return – 44 Lancasters and 34 Halifaxes – almost 10 per cent of the force. For the Halifaxes, the loss rate amongst those that had not turned back early with problems was almost 15 per cent. The Halifax Mk IIs and Mk Vs, powered by Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, were permanently withdrawn from operations over Germany after this raid. Some 420 RAF aircrew were killed and a further 131 became prisoners of war. This was the heaviest Bomber Command loss of the war up to this point, easily exceeding the 58 aircraft lost on 21st /22nd January 1943 when Magdeburg had been the main target.

Readers will know that the BBMF Lancaster PA474 is currently painted to represent a Lancaster of 460 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), based at RAF Binbrook (the original wore the serial W5005). This aircraft did not take part in the raid to Leipzig on the night of 19/20th February 1944 – perhaps it was unserviceable – although it flew the following night on an operation to bomb Stuttgart. However, 24 other 460 Squadron Lancasters did take part in the Leipzig raid; sadly two of them failed to return. One of these was Lancaster ND569, ‘AR-E’, flown by 21-year-old Flight Sergeant Stan Mackrell RAAF and his crew. His navigator and wireless operator baled out to become POWs, but the other five members of the crew, including Mackrell, were killed.

The second 460 Squadron Lancaster lost that night was JB610, ‘AR-H’, flown by newly-commissioned Pilot Officer Ken Godwin RAAF and his crew of three other Australians and three British airmen, who were on their eighth operation. They had already had a miraculous escape on the night of 16/17th December 1943, ‘Black Thursday’. (The story of that night, when low cloud and fog caused the loss of 43 heavy bombers in crashes over England, was the subject of an item for the Club newsletter in December.) Godwin and his crew flew JB704 to Berlin and back that night, despite having to feather an engine outbound over the Dutch coast, continuing on three at the reduced altitude of 17,000 feet to bomb the target. On returning to Binbrook, short of fuel and attempting to land in fog, JB704 hit the ground a few fields short of the runway, wrecking the aircraft. Miraculously, all the crew survived, more or less unscathed. However, their luck was to run out on 19/20th February.

At 19,000 feet, just north-west of Hannover, the Godwin crew’s Lancaster, JB610, was attacked from astern by a night fighter, which raked the bomber from stern to nose with a three second burst of cannon fire, starting fires in the aircraft, including a serious fire in the bomb bay which spread rapidly. It seems likely that both of the gunners were killed by the burst of fire, as neither responded on the intercom when the pilot asked if the crew were okay. The navigator, RAF Sergeant Mike Wiggins, tackled a fire on his chart table with a fire extinguisher that the flight engineer handed to him. As he did so his intercom lead became disconnected. He saw the flight engineer move down the fuselage with another fire extinguisher, apparently in an attempt to tackle the blaze. With the situation becoming hopeless and the fire impossible to control, the pilot gave the order to bale out. The bomb aimer, Warrant Officer Vernon Dellit RAAF, removed the escape hatch and was the first out. After landing by parachute Dellit hid and walked for two days before being captured whilst asleep. He spent the remainder of the war as a POW.

Navigator Mike Wiggins noticed the wireless operator, Flight Sergeant Frank Hennessey RAAF, get up from his seat just after the engineer had passed. Whilst extinguishing the fire on his desk, with his intercom lead disconnected, Wiggins had missed the bale out order. He went to follow the flight engineer to the fire amidships, but found that both the engineer and the wireless operator had disappeared. The fire was impossible to control so he returned to his desk to report to the pilot over the intercom. When he received no reply from any of the crew he looked around his blackout curtain and saw that the pilot’s seat was vacant, as was the bomb aimer’s compartment. Assuming the rest of the crew had baled out, he followed suit. Wiggins was also to spend the remainder of the war as a POW. Dellit and Wiggins were the only survivors from JB610.

A German civilian witness on the ground saw the stricken Lancaster diving down on fire, to crash in Steinhuder Meer Lake. He later reported that the bomber exploded in the air and again on impact with the lake, scattering wreckage over a large area. One wing was found in a field 1km from the lake; the rest fell in the lake. Subsequently, the bodies of the two gunners, RAF Sergeant Frank Clarkson (the mid-upper gunner) and rear gunner Flying Officer John Morris RAAF, were found, Clarkson on the edge of the lake and Morris in the lake, presumably having been blown out of the Lancaster when it exploded in the air. They were both buried in the local church cemetery, but now rest in the Hannover War Cemetery. The three other crew members bodies were assumed to still be in the wreckage in the lake which was left undisturbed, eventually sinking into the mud under the water.

The navigator’s post-war report, after being repatriated from POW camp, suggests that the pilot was not in his seat when the navigator left the aircraft. This created some doubt over whether Ken Godwin had in fact baled out. However, detailed post-war investigations failed to find any trace of him and he, flight engineer RAF Sergeant Cyril Wood and wireless operator Frank Hennessey are remembered on the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede for all those with no known grave.

It does no harm to remember the dire circumstances facing the free world 75 years ago and the nightly heroics of the men of Bomber Command in taking the fight to the enemy, often at huge personal cost. It is a pity that the person or persons responsible for the recent defacing of the Bomber Command Memorial in Green Park, London, cannot understand that.

Lest we forget