Peenemunde – Bomber Command veteran returns

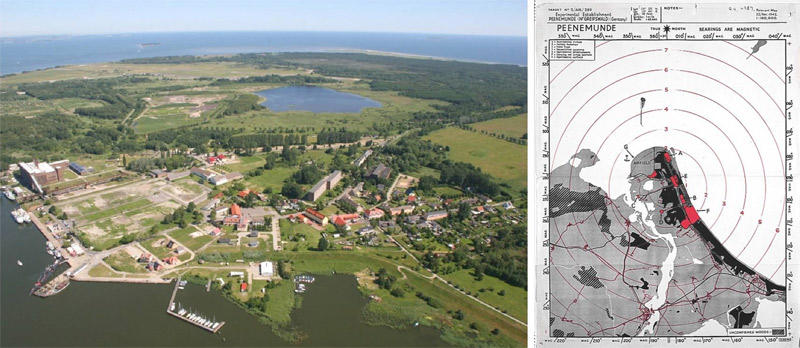

Header image: The Historical Technical Information Centre at Peenemunde, as it is today, on the site of the Nazi ‘V’ weapon, rocket research and testing centre. This was the target for a major Bomber Command raid in August 1943.

During 1943 intelligence data and photo-reconnaissance images gathered by the British about the secret research and development work being conducted by the Germans at Peenemunde on the Baltic coast, including development of the V1 ‘doodlebug’ flying bomb, the V2 long-range guided ballistic missile and rocket powered fighters, made the site a priority target for RAF Bomber Command. Because Peenemunde was some 600 miles from the most easterly British airfield, the earliest date when there would be sufficient cover of darkness was mid-August. The raid also needed to be carried out in bright moonlight to improve accuracy and increase the chances of success. The night of 17-18th August was set as the date for the raid on Peenemunde.

A total of 596 Bomber Command aircraft participated in the raid: 324 Avro Lancasters, 218 Handley Page Halifaxes and 54 Short Stirlings. The crews were not briefed on the exact nature of the target, being told that Peenemunde was being used by the Germans to develop radar that promised to greatly improve their night air defence organization (a direct threat to the Bomber crews). The Operation Order stressed the importance of the raid by stating: “If the attack fails…it will be repeated the next night and on ensuing nights regardless, within practical limits, of casualties”. The primary objective was to kill as many of the personnel involved in the research and development as possible. Secondary objectives were to damage the research facility and destroy the related work and documentation. With this in mind there were three specific aiming points: scientists’ and workers’ living quarters, the rocket factory and the experimental station.

Right: RAF target map of Peenemunde.

Though Peenemunde was a sprawling facility, spread over some 9.6 square miles, it was still small compared with most Bomber Command targets of the time; it was also protected by smoke screens. For precision, the crews would bomb from 7-9,000 feet instead of the more normal altitude of around 18-19,000 feet. Pathfinders would mark the aiming points and a Master Bomber was also used for the first time. A Mosquito diversion to Berlin was mounted to draw off the German night fighters and this was successful for the first waves of heavy bombers, but unfortunately not for the last wave.

The first bombs began to fall on Peenemunde at 00:35 on 18th August. The raid was successful to a degree, although bombing was not as accurate as would have been ideal and most of the important German scientists survived, with only two being killed. Post-war research generally agrees that the raid delayed the work at Peenemunde by about two months. To put that into perspective, once the V1 flying bombs began to be launched against Britain from 13th June 1944, with the V2 rockets following from 8th September that year, they were fired at an average rate of about 300 V1s and 230 V2s per month. The missiles typically caused some 1,400 deaths per month in England, with over 3,500 people injured each month, so by setting the German weapon programme back by two months many lives were saved by the Bomber Command raid on Peenemunde.

Right: 168 people died in New Cross, London, on 25th November 1944 when a V2 ballistic missile hit a Woolworths department store crowded with Saturday morning shoppers.

Bomber Command’s losses on the raid totalled 40 aircraft: 23 Lancasters, 15 Halifaxes and 2 Stirlings; 6.7 per cent of the force dispatched. 243 Bomber Command aircrew were killed, whilst some crew members from shot down bombers became POWs. Most of the casualties – 29 aircraft – were suffered by the last wave when the German night fighters arrived in force, once they realised that the Berlin raid was a ‘spoof’. This was the first night on which the Germans used their new Schräge Musik weapons, twin upward-firing cannons fitted to Me110s. Two Schräge Musik night fighters found the bomber stream flying home from Peenemunde and are believed to have shot down six of the bombers lost on the raid.

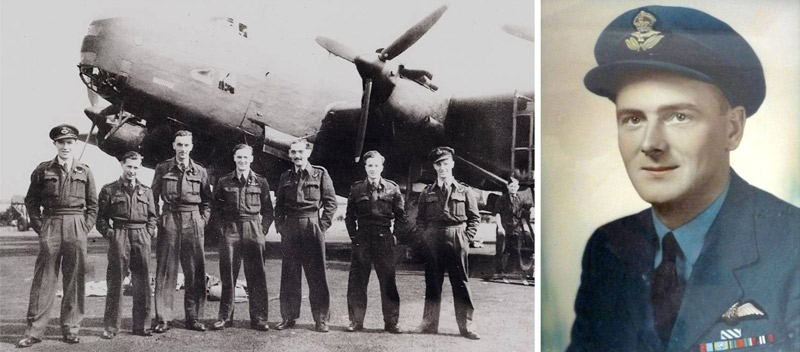

Right: George Dunn in wartime. He was 20 years old at the time.

One of the RAF bomber pilots who participated in the Peenemunde raid in 1943 is a good friend of the BBMF, having visited the Flight on numerous occasions and attended many BBMF events. Flight Lieutenant George Dunn DFC Ld’H, who was a 20-year-old Halifax pilot and captain on the raid, is now 95. On 17-18th August 1943 he flew a 76 Squadron Halifax bearing the code letters ‘MP-G’ from Holme-on-Spalding-Moor, bombing the target as part of the first wave at 00:20 hours. George's recollections of the raid are still crystal clear, from the briefing when the crews were told "if you don't do the job tonight, you'll got back tomorrow, the day after that and the day after that, until the job is done"; to the run-in to the target, which he bombed from 7,000ft in bright moonlight. He also recalls how fortunate he and his crew were that a late change of plan switched his squadron from the last wave to the first, in the knowledge that most of those who failed to return were on the last wave. George flew a total of 44 ‘ops’ during World War Two, 30 in Halifax bombers and 14 in Mosquitos bombing Berlin. After the war he continued to fly for the RAF until 1947, testing a number of aircraft types including Mosquitos, Spitfires, Hurricanes and Mustangs for a maintenance unit in Ismailia, Egypt.

Right: George at Peenemunde in August (with a V2 flying bomb behind him), almost exactly 75 years since he last visited it at the controls of a Halifax bomber.

Last month, almost exactly 75 years after he had last visited Peenemunde at the controls of a Halifax bomber, George made an emotional return to the scene of the raid for the first time. His trip and flight out and back were organised by Graham Cowie of Project Propeller, which flies World War Two veteran aircrew to a reunion each year, and was made possible by the generosity of Jason Carley who flew George in his Cessna citation business jet. George explored the Peenemunde Historical Technical Museum, saw the remains of a shot down Lancaster that lies in a nearby lake, and laid a wreath at the cemetery at Griefswald where the casualties of the night are buried, to commemorate all the victims, Allied, German and slave labourers of various nationalities. He said, “I knew it was a special operation and there were also many civilian casualties. I never dreamt I would be able to make this trip, but I wanted to come back to commemorate them all."