Bomber Command Battle of Berlin

Header image: Lancasters in the bomber stream with enemy searchlights seeking them out.

Seventy-five years ago this month, in November 1943, Royal Air Force Bomber Command, under Air Chief Marshal Arthur 'Bomber' Harris, launched the second phase of an airborne bombing campaign against the German capital city that lasted to March 1944 and became known as the Battle of Berlin. Harris believed that the aerial assault on Berlin – if it came anywhere close to Hamburg’s terrifying destruction in July 1943 – could break German resistance and bring an early end to the war. “It will cost us between 400 and 500 aircraft”, he said. “It will cost Germany the war”. During the campaign period, attacks were not solely limited to Berlin, which endured 16 massive raids; other German cities were bombed too, to prevent the enemy concentrating its forces in defence of Berlin.

Right: Artist’s impression of Lancasters bombing the ‘Big City’. (Piotr Forkasiewicz)

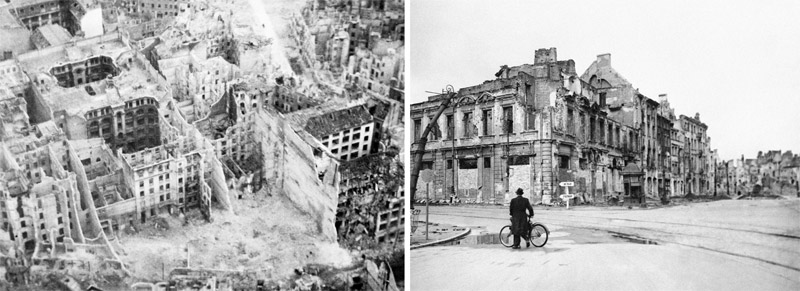

The first raid of the campaign, on 18-19th November 1943, by 440 RAF bombers did little damage to the German capital, but the second major attack on the night of 22nd-23rd November proved to be the most effective raid on Berlin of the war. 469 Avro Lancasters, 234 Handley Page Halifaxes, 50 Short Stirlings and 11 DH Mosquitos (764 bombers in total) dropped 2,300 tons of bombs in 30 minutes, killing 2,000 Berliners and rendering 175,000 homeless. Several firestorms ignited and it was during this raid that the landmark Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church was destroyed. The following night 1,000 more Berliners were killed and 100,000 rendered homeless. Regular raids in December 1943 and January 1944 killed hundreds of people each night, leaving 20,000 to 80,000 homeless each time.

The Battle of Berlin diverted German military resources away from other theatres of war and had an economic effect, in physical damage, worker fatalities and injuries, relocation and fortification of industrial buildings and other infrastructure, but the campaign failed to force a German capitulation. Reducing Germany’s capital to rubble from the air did not deliver the knockout blow predicted. In the same way that the morale and spirit of Londoners and occupants of other British cities had not been broken by the German blitzes earlier in the war, these attacks on Berlin did not break the Germans’ morale either. In March 1944 the bombing offensive against Berlin was called off in favour of attacking other targets.

RAF Bomber Command flew 9,111 sorties against Berlin with the loss of 492 aircraft – mostly four-engine heavy bombers – and 954 damaged or written off, a loss rate of 5.8 per cent (exceeding the 5 per cent loss rate deemed acceptable by Bomber Command). More than 3,500 Bomber Command were killed or captured during the Battle of Berlin. For the men of RAF Bomber Command this was a particularly tough and dangerous period of the war.

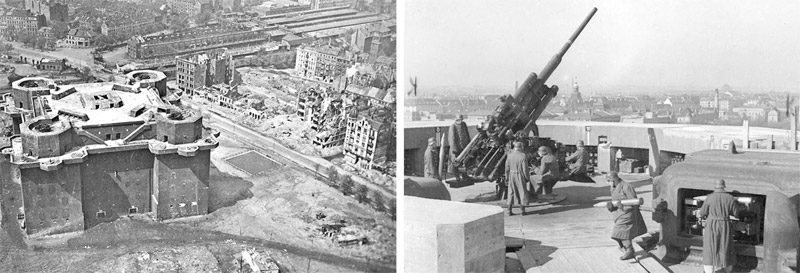

A combination of size, geography and an extensive system of active and passive defences made Berlin the most dangerous target in Germany. The long flight to the ‘Big City’ – typically over 1,000 nautical miles there and back – was not popular with the bomber crews who knew what to expect. Berlin was ringed with a flak belt 40 miles wide and a searchlight band over 60 miles across. The defences centred on 24 128-mm anti-aircraft guns grouped in eight-gun batteries on massive flak towers. Only the Ruhr region was more heavily defended. Not only was it well defended, but a large part of the route across Germany to Berlin was also infested with anti-aircraft guns. Berlin’s position made it relatively easy for the enemy to guess that it was the target if the bombers were tracking in that direction, and the night fighters could be positioned in readiness. Although the longer hours of darkness during the winter nights helped protect the bombers, the predominantly cloudy winter weather created hazards for flying and meant it was difficult to see the target to bomb accurately.

Right: An anti-aircraft gun on top of a flak tower.

When the RAF bomber aircrew arrived over Berlin they were struck by the magnitude of the city itself and the resistance offered by her defenders. One described the sight as awesome, citing the “immensity of the city” and his apparently “excruciatingly slow progress across it”. For another, flying through the formidable flak defence, it was as though a “giant hand” took hold of the aircraft and shook it, like a huge dog shaking a rat. When cloud cover was heavy, rendering searchlights useless, the Germans released lanes of fighter flares above the bomber stream, to illuminate them for the night fighters. Some RAF airmen claimed they could do the newspaper crossword by them! Another cheekily said flying through them was “like running naked through a busy railway station”, hoping no one would notice.

460 Squadron RAAF Lancaster W5005 ‘AR-L’ for Leader, now represented by the port side colour scheme of BBMF’s PA474, went to Berlin four times from Binbrook during this period, sorties that typically lasted seven and a half hours according to the operational records, and that were subsequently marked on her bomb log with red bomb symbols. 460 Squadron lost a total of 36 aircraft with their seven-man crews during the Battle of Berlin.