14th March 1945 - First 'Grand Slam' raid

Header image: 617 Sqn Lancaster B1 Special PB996 ‘YZ-C’ releases a 21,500lb ‘Grand Slam’ over the Arnsberg Viaduct, Germany, on 19th March 1945.

The first of the enormous British ‘Grand Slam’ ‘earthquake’ bombs were dropped in anger 75 years ago this month.

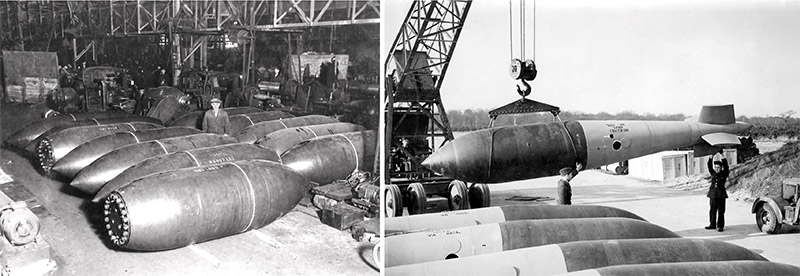

‘Grand Slam’ was the ‘big brother’ of the ‘Tallboy’ which had been used by IX and 617 Squadrons since June 1944 mainly against hardened concrete bunkers, including ‘V’ weapon sites, and which famously sunk the German battleship Tirpitz in November 1944. Both the 12,000lb ‘Tallboy’ and the 21,500lb ‘Grand Slam’ bombs were products of the innovative mind of scientist and inventor Barnes Wallis. The 10-ton ‘Grand Slam’ was officially known as ‘Bomb, MC (Medium Capacity) 22,000lb’; it was just over 25 feet (almost 8 metres) long and almost 4 feet (1.2 metres) in diameter, and contained 9,135lb of Torpex explosive. The bomb casings were produced by Vickers & Co, Sheffield, at their River Don Works. Like the Tallboy, after hot molten Torpex was poured into the casing, the explosive took a month to cool and set.

Right: Complete ‘Grand Slams’ being moved from the bomb dump at Woodhall Spa.

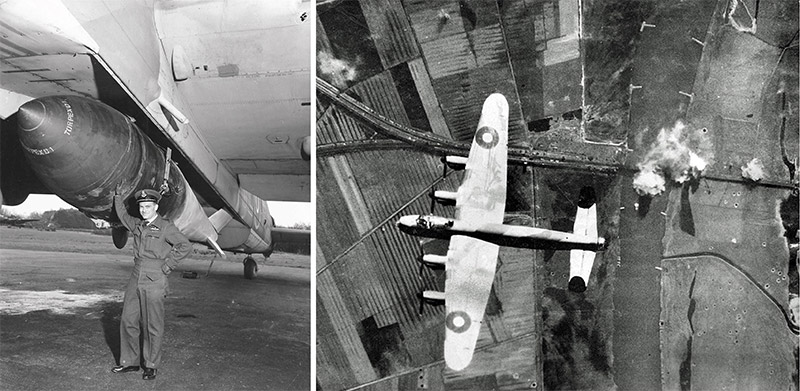

‘Grand Slam’ could be carried only by specially modified Lancasters – B1 Specials – operated by 617 Squadron. The B1 Specials had the bomb bay doors removed entirely so that a single ‘Grand Slam’ could be carried semi-recessed under the belly of the aircraft, and the undercarriage was strengthened. The front gun turret and mid-upper gunner’s turret were removed and faired over to reduce weight. The standard crew for a B1 Special was five men with no mid-upper gunner and no wireless operator. The B1 Specials could also carry and drop the smaller ‘Tallboy’ bomb.

The prototype ‘Grand Slam’ was dropped from a B1 Special Lancaster, flown by a test pilot from the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment, at the Ashley Walk range, near Fordingbridge in the New Forest, on 13th March 1945. It made a crater 130 feet in diameter and 70 feet deep. Later that same day, when news of the successful trial of the ‘Grand Slam’ had reached Woodhall Spa, 617 Squadron’s base, two Lancaster B1 Specials, each loaded with one of the huge bombs, took off, one flown by the C.O., Group Captain ‘Johnny’ Fauquier, and the other by Squadron Leader Charles ‘Jock’ Calder. Their target was the Bielefeld railway viaduct in Germany. Due to heavy cloud over the target area the raid was aborted and none of the 19 Lancasters involved dropped their weapons. With their ‘Grand Slams’ still on board, Fauquier and Calder landed back on the long runway at Carnaby airfield, near Bridlington, Yorkshire, where the runway was five times the normal width and 9,000 feet long.

The raid was rescheduled for the afternoon of the following day, 14th March. As Fauquier and Calder prepared to take off, the C.O.’s aircraft developed a mechanical fault during the engine run-ups. Knowing that history was about to be made, Fauquier raced towards Calder’s aircraft to commandeer it. The Scotsman, however, was one step ahead and taxied out and took off, feigning cheerful ignorance of the C.O.’s intentions. He joined up with 14 other ‘Tallboy’-carrying Lancasters of 617 Squadron and their escort of P-51 Mustang fighters for the daylight raid. A DH Mosquito of 627 Squadron was also present to film the attack.

Right: Lancaster B1 Special PB996 ‘YZ-C’, flown by Sqn Ldr ‘Jock’ Calder, drops a ‘Grand Slam’ against the Arbergen railway bridge over the River Weser on 21st March 1945.

At 4.30 pm Calder released the 10-ton ‘Grand Slam’ from 12,000 feet against the two parallel railway viaducts at Bielefeld. This was lower than ideal, but forced by the cloud base. The Lancaster, PD112, leapt up 500 feet as the bomb was released. A dozen ‘Tallboys’ were also dropped by the rest of the squadron, but it was the ‘Grand Slam’, fuzed for an 11-second delay, that did the damage. It hit the ground vertically about 80 feet from one of the viaduct pillars at near supersonic speed and penetrated deep underground before exploding, creating a 100-foot crater. The resulting ‘camouflet’ or cavern undermined the viaduct’s foundations.

When the dust and smoke had cleared, more than 400 feet of both viaducts, five arches, had been brought down by the ‘earthquake’ effect. The ‘Grand Slam’ had achieved what more than 3,500 tons of bombs dropped on the viaduct in 54 attacks up to this point had failed to do. The viaduct was closed for the rest of the war, significantly degrading the enemy’s ability to move troops and supplies by rail through the area.

A total of 41 ‘Grand Slams’ were dropped before the war ended.