Coningsby Lancaster lost on D-Day

Header image: In a moonlit night sky a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 climbs unseen in the blind spot under a Lancaster’s tail, before delivering a devastating burst of cannon fire.

A Lancaster of 97 (Pathfinder) Squadron from RAF Coningsby – now the home of the BBMF Lancaster – was amongst the first RAF casualties of D-Day, 80 years ago on 6th June 1944.

When the Lancaster crews were briefed at Coningsby on the 5th June for the operation that night to bomb a battery of coastal heavy guns on the French coast at a point called St Pierre du Mont, on the south-east corner of the Cherbourg Peninsula, details such as information on convoys in the English Channel and impending naval operations, confirmed for the crews that this was the start of the long-awaited Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied France that they all wanted to be part of. The commanding officer of 97 Squadron, 24-year-old Wing Commander Edward James ‘Jimmy’ Carter DFC, was heard to exclaim, “Thank God I’m still on ops and not at an OTU [Operational Training Unit]”. He was not to know it, but his determination to be involved in the great enterprise was going to cost him his life.

‘Jimmy’ Carter had been in the RAF throughout the war; he was now a very experienced bomber pilot, with a DFC ribbon on his chest, awarded for a previous tour of operations. He had assumed command of 97 Squadron in January 1944, when it was based at Bourn, and had moved with the unit to Coningsby in April 1944. Since taking over the Squadron Carter had led 97 Squadron’s crews on Pathfinder, target marking operations to many targets in Germany. For the operation on 6th June, Carter was nominated as the Deputy Master Bomber.

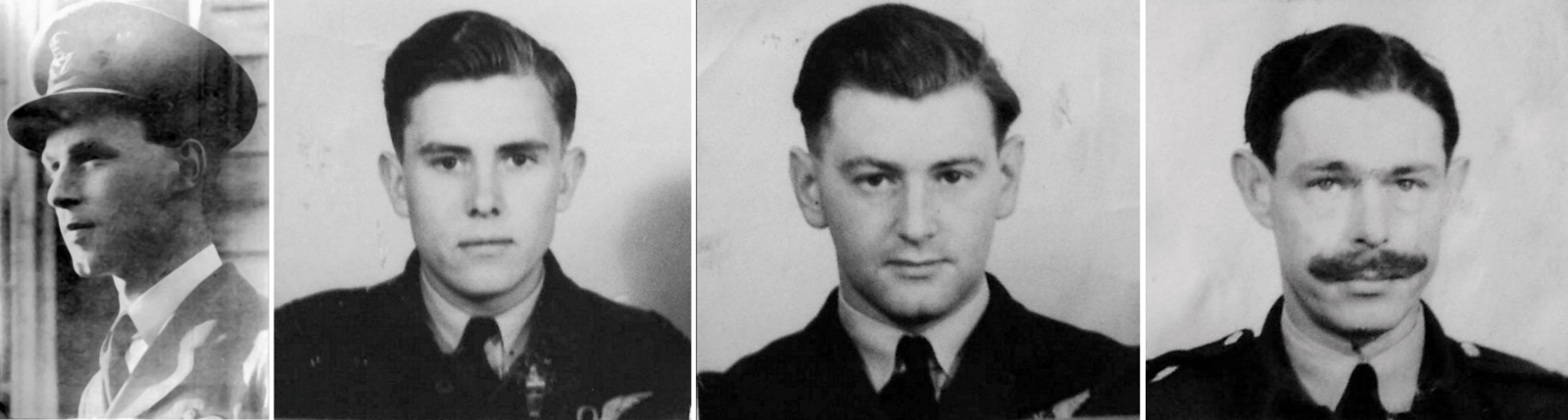

Carter’s crew were at least as experienced and decorated as their pilot and captain; they boasted no less than nine Distinguished Flying Crosses or Distinguished Flying Medals between them. The crew consisted of: Pilot Officer Guy Dunning DFM (flight engineer), Flight Lieutenant Ron Conley DFC RAAF (navigator), Flight Lieutenant Herbert Rieger RCAF (bomb aimer), Flight Lieutenant Albert Chambers DFC and Bar (wireless operator) who had flown 58 ops, Warrant Officer Frank Watson DFM (mid-upper gunner) and Squadron Leader Martin Bryan-Smith DFC and Bar (rear gunner). Two of the most experienced of these crew members were the Gunnery Leader and the Signals Leader on the squadron. It was not uncommon for Pathfinder Lancasters to carry an eighth crew member on some ops, who sat alongside the navigator and operated the H2S ground mapping radar for blind bombing and accurate target marking. This was the case in Carter’s aircraft on the night of 6th June and Flying Officer ‘Hank’ Jeffery DFM flew with the crew as the second navigator/bomb-aimer in this role, as he had done on a previous occasion. This crew which was, at the time, probably one of the RAF’s most decorated, was also a very valued team of experts.

Eighteen Lancasters of 97 Squadron were launched on the operation from Coningsby in the early hours of D-Day, 6th June. Carter and his crew were flying Lancaster B.III ND739, ‘OF-Z’. They must have been feeling good about their chances as they lifted off from Coningsby’s runway at 02:56 because the target was barely inside enemy territory and their exposure to enemy defences, ‘flak’ and night fighters was surely only going to be brief.

Across the Channel, at Évreux airfield in Normandy, German night-fighter pilot Hauptmann Helmut Eberspacher of 1./SKG10 was sitting on alert. SKG10 was a Luftwaffe fast-bomber, ground-attack unit equipped with Focke-Wulf Fw 190 G-3s and G-8s. Eberspacher, the holder of the Iron Cross first and second class, had been promoted to Staffelkapitän to lead the 3rd Staffel of the 1st Gruppe in May. SKG10 flew ‘hit and run’ fighter-bomber missions with their Fw 190s over southern England by day and by night. Due to the lack of regular night fighters in France and in view of the increasing number of night bombing missions being flown by the RAF against French targets, from April 1944 the Fw 190s of SKG10 were also employed on ‘Wilde Sau’ (Wild Boar) free-ranging, night-fighter missions against the British bombers on brighter moonlit nights. It was for this purpose that Eberspacher and some of his pilots were sitting on alert at Évreux.

At about 04:30 information reached the German Gruppe HQ that Allied bombers were pounding the coast between Carentan and Caen. Eberspacher was scrambled with three other Fw 190s into that sector. There was very limited assistance from the German fighter controllers whose radars had mostly been destroyed, whilst the surviving parts of the air defence system were being heavily jammed. However, there were so many RAF bombers in such a small area that it was almost inevitable that the Fw 190 pilots would stumble across some. Fate was about to bring Eberspacher’s Fw 190 and ‘Jimmy’ Carter’s Lancaster together.

Carter and his crew had dropped their bombs on the target and had turned for home when they were found by Eberspacher in his Fw 190 shortly after 05:00. The bomber crew probably never saw the Fw 190 and never knew what hit them. Eberspacher spotted several Lancasters silhouetted against the moonlit clouds below him. He dived down on Carter’s ‘Z-Zebra’ and attacked from the Lancaster’s blind spot underneath, avoiding engaging the bomber from any other angle out of a healthy respect for the RAF gunners. At 05:04 a transmission from Carter on the Force radio frequency, acknowledging a message from the Master Bomber, was suddenly cut short. Cannon shells and machine gun fire from the Fw 190 ripped into the underside of the Lancaster, causing immediate catastrophic damage, probably wounding and killing some on board and setting the bomber on fire. It is almost impossible to imagine the adrenalin-pumping terror that would be felt by a bomber crew on the receiving end of a sustained burst of cannon-fire from a completely unseen foe.

Eberspacher reported no return fire from the Lancaster and knew it was fatally damaged. He immediately attacked a second Lancaster and then a third, shooting down all three within three minutes, with the loss of all on board except one of the gunners. One of the other pilots in his flight, Feldwebel Eisele, claimed another of the RAF heavy bombers, so when they landed back at Évreux they were able to claim a total of four bombers shot down, the first air combat action and the first kills for the Luftwaffe on D-Day.

None of Carter’s crew escaped from the burning Lancaster; the bombing height was lower than usual and there was little time for any survivors of the Fw 190 attack to bale out before the bomber ploughed into the Normandy fields and exploded. All eight of the crew were still on board and all were killed. If proof was needed that experience, expertise and skill were not enough to survive the bomber crews’ war, this was surely it. The Carter crew were lost without trace. Most of the RAF bomber crewmen who were killed over enemy territory during the Second World War were given a decent burial by the Germans. However, in this instance the location of the crash site, near Carentan in Normandy, rapidly became a battlefield after the D-Day invasion. The war rolled over the site and the men’s remains were never recovered. Their names were listed on the Runnymede memorial which commemorates 20,389 airmen of the Second World War with no known graves. Their victor, Helmut Eberspacher, was awarded a coveted Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross in January 1945 after he had flown 170 fighter-bomber and night-fighter missions and shot down seven enemy aircraft. He survived the war and died in June 2011.

In 2012, the crash site of Lancaster ND739 ‘Z-Zebra’ was located and excavated. A local metal detectorist had found a gold ring, which bore the initials ‘AC’ on its face, and the inscription ‘Love Vera’ engraved on the back. Some detective work by British aviation historian and archaeologist Tony Graves led him to realise that the ‘AC’ referred to Albert Chambers (Carter’s wireless operator) who had married 21-year-old Vera Grubb in October 1943, just eight months before he died on D-Day. The fragmentary wreckage that emerged from the excavations convinced the aviation archeologists that these were the remains of ND739, Wing Commander ‘Jimmy’ Carter’s Lancaster, which had been missing from Coningsby since 6th June 1944. Several personal items found during the dig were the most poignant: a silver-plated cigarette case twisted by the impact, a watch torn from the wrist of an airman, a mangled Bomber Command whistle, a forage cap, a silk flying glove, and remains of wool serge battledress jackets, one with a DFM ribbon, one with the remains of a Waterman pen in the pocket and one with a German 7.92 bullet lodged inside a sleeve. Lancaster ND739 and some personal reminders of its crew had finally been found 68 years after they went missing on D-Day.

Lest we forget