Sinking the Tirpitz – 12th November 1944

Header image: Lancasters of 617 Sqn and IX Sqn dropping ‘Tallboy’ bombs on the German battleship Tirpitz in Tromso Fjord, Norway, on the morning of 12th November 1944. (Artwork: Jim Laurier)

Seventy-five years ago this month, on 12th November 1944, 18 Avro Lancasters of 617 Squadron and 13 from IX Squadron took off in darkness from Lossiemouth and Milltown airfields in northern Scotland, to head north east towards the Norwegian Sea and the Arctic Circle on what was to be an epic flight both in duration and effect. This was to be the final attack on the German battleship Tirpitz, moored in Tromso Fjord, Norway, 190 miles inside the Arctic Circle. This particular operation, the last of many against the great ship, had been codenamed ‘Operation Catechism’ and was led by the C.O. of 617 Squadron, Wing Commander ‘Willie’ Tait DSO and three Bars DFC and Bar.

The Lancasters had been specially modified with the removal of their mid-upper gun turrets and other equipment to lighten them, and they flew with a crew of six rather than the usual seven men. Carrying extra fuel - 2,406 gallons each, 252 gallons more than the usual maximum fuel load for a Lancaster – and a massive 12,000-lb ‘Tallboy’ bomb in their bulged bomb bays, their all-up weight was 68,200 lbs (31,000 kg) on take-off. The Lancaster bombers were accompanied by an additional film-unit Lancaster of 463 Squadron RAAF, fitted with two long-range 400-gallon capacity fuel tanks in the bomb bay, and cameras to record the results of the raid.

The 32 Lancasters flew past the Shetland Islands and continued north east towards Norway. On reaching 64 degrees north, the force turned onto a more easterly heading, crossing the Norwegian coast at low level through a potential gap in the enemy’s radar cover. They then climbed to clear the mountains and flew on towards Sweden. Turning north just on the Swedish side of the Norwegian/Swedish border, with scant regard for the latter nation’s neutrality, they rendezvoused at the assembly point, a lake inside Sweden about 100 miles south east of Tromso, as the Arctic dawn broke. From here the track to the target would, it was hoped, surprise the Tirpitz and beat her smoke screen.

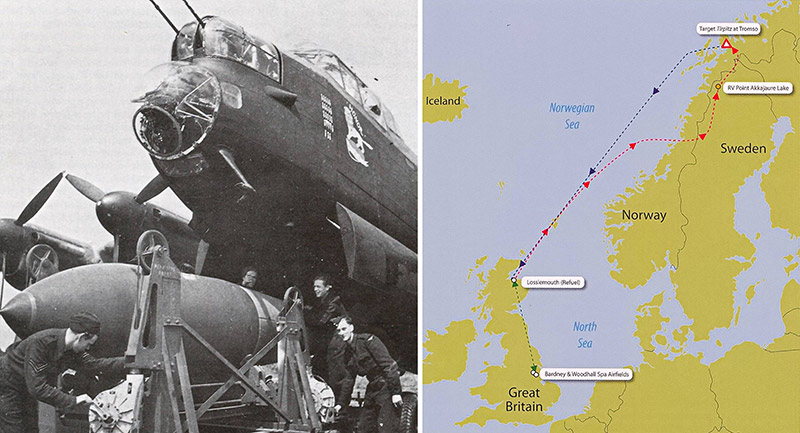

Right: The 2,200 miles route from Lossiemouth to Tromso Fjord and back as flown by the ‘Operation Catechism’ Lancasters on 12th November 1944.

The famous, huge, beautiful and potentially deadly German battleship Tirpitz had been a priority target for the Allies since 1940. Her sister ship, Bismarck, had shown the power of this class of battleship when, on 24th May 1941 during the Battle of the Denmark Strait, she sank the Royal Navy’s similarly-sized battle cruiser HMS Hood, which exploded shortly after being hit by shells from Bismarck, fired from 10.3 miles (16.6km). There were only three survivors from Hood’s crew of 1,418 officers and men. The British and the Allies had good reason to fear the Tirpitz. Between July 1940 and February 1941, RAF Bomber Command carried out 17 attacks against the battleship at Wilhelmshaven, whilst Tirpitz was being fitted out, but no hits were scored. From then on, up to this final raid in November 1944, the great ship was hunted, hounded and attacked at its various Norwegian moorings by RAF and Royal Navy aircraft on 15 occasions, by a total of almost 400 aircraft, and also by RN two-man underwater ‘chariots’ and midget submarines. The last underwater raid, which earned the Victoria Cross for two of the ‘X-craft’ commanders, had severely damaged the warship, compromising its ability to operate to full capacity at sea, although the Allies did not know this. Now, after a previous Lancaster ‘Tallboy’ attack which damaged her further, the Germans had moored Titpitz in Tromso Fjord as a semi-static heavy artillery battery and she was just in range for an out-and-back raid by the modified Lancasters from the UK mainland.

At zero hour on 12th November 1944, the Lancasters set course on the long straight run-in to the target – needed by the bomb sights to ensure accurate bombing – followed by a ‘gaggle’ of Lancasters at 12,000 to 16,000 feet. The Lancaster crews could clearly see the Tirpitz from 20 miles in the clear and cloudless conditions. There was no sign of any of the Luftwaffe FW190 fighters, which had recently been moved to Bardufoss, 40 miles away. In fact, confusion amongst the German forces meant that the fighters were scrambled too late to interfere with the Lancasters’ attack. The unexpected attack direction had indeed caught the German defences by surprise. As the Lancasters came into view to those on the surface, the guns on the battleship itself, from two ‘flak’ ships and from anti-aircraft batteries on the shore, opened fire, their shells dotting the sky with ugly orange clouds. Willie Tait described the environment as “not healthy”; other crews thought that the long straight bombing run seemed “interminable”. The first ‘Tallboys’ were dropped at 08:41GMT and in the next eight minutes 29 of the huge bombs rained down, some with great accuracy.

Tirpitz was hit by at least two ‘Tallboys’ and possibly by a glancing blow from a third. In addition, two more bombs were very near misses. Catastrophic damage was caused by the two direct hits, which smashed into the port side of the ship; the explosions tore a hole 200 feet long in the port side of the hull. Hundreds of tons of water flooded the battleship, she listed 35 degrees to port and then steadied as she jammed against a bank of mud on the bottom of the fjord. The near misses probably cratered the sea bed and took water away from the side of the ship, aggravating the situation and the ship’s list increased to about 60 degrees. At 08:51 GMT there was an enormous explosion in the ammunition store beneath ‘C’ turret, which blew the 700-ton turret up and out, arcing 25 yards into the water. Almost immediately Tirpitz capsized to an angle of about 135 degrees, so that about 10 minutes after the first bomb had dropped only her upturned hull was visible from the air, as recorded by the film unit Lancaster. Most sources estimate that of the 1,700 men who made up the crew of Tirpitz, between 940 and 1,204 were lost, many of them trapped in the upturned hull. Miraculously, 87 of the sailors were rescued by cutting holes in the ship’s hull to reach them.

One of the IX Squadron Lancasters, LM448, was hit by ‘flak’ and, unable to make the return flight all the way home, crash-landed in Sweden, where the crew was interned. The long return flight for the remaining Lancasters was unchallenged by the enemy, but lengthened by adverse wind conditions and, on arrival, low cloud at Lossiemouth caused several of the Lancasters to divert to alternate airfields. The return trip was over 2,200 miles and the Lancasters had been airborne for more than 12 hours. The film unit Lancaster from 463 Squadron, with its overload fuel tanks in the bomb bay, returned direct to Waddington, landing 14 hours after it took off!

The extended, violent and costly campaign to sink the Tirpitz was finally over. The remarkable Avro Lancaster and Barnes Wallis’ incredible weapon – the ‘Tallboy’ bomb – had finally defeated the mighty battleship.