RAF Bomber Command’s first 1,000 bomber raid May 1942

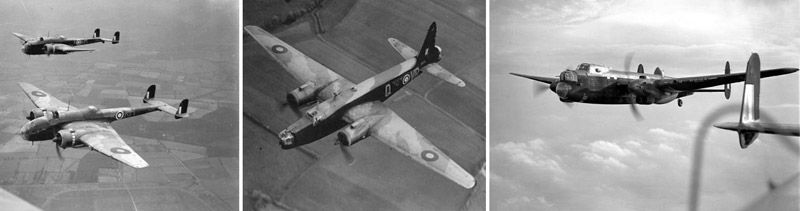

Header image: Vickers Wellingtons made up the majority of the force that took part in the RAF’s first 1,000 bomber raid. Some were from Operational Training Units, such as these from No 16 OTU at RAF Barford St John, a satellite airfield for Upper Heyford. (artwork: Gary Eason flightartworks.com)

RAF Bomber Command’s first 1,000 bomber raid – codenamed Operation Millennium – took place 75 years ago this month on the night of 30th/31st May 1942.

The psychologically important and newsworthy figure of 1,000 bombers was not easy to achieve. At this stage of the war RAF Bomber Command had a front line strength of around 400 aircraft, mostly twin-engine bombers, with a predominance of Vickers Wellingtons. In May 1942 there were only four operational squadrons fully equipped with the new four-engine Avro Lancaster heavy bomber.

Right: There were only four operational Lancaster squadrons in May 1942, with a fifth in the process of converting from Manchesters to Lancasters.

The Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command, Air Marshal Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, eventually managed to assemble a force that exceeded the ‘magic number’. Every spare aircrew member and aircraft was gathered in by the operational squadrons, and Bomber Command’s operational training units (OTUs) were also ordered to commit every available operationally-capable aircraft. These OTU aircraft were crewed by a combination of instructors, many of them ex-operational aircrew on ‘rest tours’, and aircrew in the later stages of their courses who were not yet fully trained. Every effort was made to provide the crews under training with at least an experienced pilot, but 49 aircraft from the OTUs took part with pupil pilots flying them. In view of the fearful risk of sending out so many untrained and inexperienced crews and the potential for immense losses, this was a huge gamble. When Churchill and Harris discussed the possible casualty figures, Churchill said that he would be prepared for the loss of 100 aircraft.

Eventually, on 30th May 1942, 1,047 bombers took off to bomb Cologne, the third largest city in Germany. This force was more than two and a half times greater than any previous single night's effort by Bomber Command up to this point of the war. It comprised: 602 Vickers Wellingtons, 131 Handley Page Halifaxes, 88 Short Stirlings, 79 Handley Page Hampdens, 73 Avro Lancasters, 46 Avro Manchesters and 28 Armstrong-Whitworth Whitleys.

The tactics that were used for this mass bombing raid were to form the basis for Bomber Command main force operations for the next two years and some elements would remain in use until the end of the war. The major innovation was the introduction of a bomber stream in which all aircraft would fly by a common route and at the same speed to and from the target, each aircraft being allotted a height band and a time slot in the stream to minimize the risk of collision. The recent introduction of the radio navigation aid ‘Gee’ made it easier for the crews whose aircraft were equipped with it to navigate within the precise limits required for such flying. The operation was led by experienced crews with ‘Gee’ equipped aircraft from Nos 1 and 3 Groups.

The intention was that the bomber stream would pass through the minimum number of German radar night-fighter boxes in the minimum time, swamping the defences as the German controllers could only direct a maximum of six potential night-fighter interceptions per hour in each box. Over the target, where earlier in the war four hours had been allowed for raids by only 100 aircraft, a mere 90 minutes was planned for 1,000 aircraft to bomb. This, it was hoped, would swamp the ‘flak’ defences at the target and deliver such a concentration of blast and incendiary bombs in a short period that the fire services would be overwhelmed.

This first 1,000 bomber raid was considered a success; it made its mark on history and it was a turning point for RAF Bomber Command in the war, setting the tone and tactics for future operations. The effects on the ground at Cologne serve to highlight the horror of war on this scale. Two and a half thousand separate fires were started, 1,700 of which were classed by the German fire brigade as "large". Almost 13,000 buildings were destroyed of which over 2,500 were industrial or commercial buildings. The number of people killed on the ground in Cologne was remarkably low, less than 500, presumably a testament to the air raid shelters. However, over 5,000 people were injured and over 45,000 were “bombed out” of their homes. It was subsequently estimated that between 135,000 and 150,000 of Cologne’s population of nearly 700,000 fled the city after the raid.

The RAF lost 41 aircraft, 22 of them over or near Cologne, of which 16 were shot down by ‘flak’, four by night fighters, and two were lost in a mid-air collision. The total losses exceeded the previous highest of 37 aircraft on the night of 7/8th November 1941 when a large force was sent out in bad weather conditions, but the proportion of the force lost in the Cologne raid – 3.9 per cent of the bombers sent on the raid – though high, was deemed acceptable. Interestingly, the highest losses were suffered by the first waves of bombers, those with the operational and experienced crews, whilst the training aircraft and those crewed by pupil crews suffered lower casualties, indicating that the German defences had become increasingly overwhelmed as the raid went on. Flying Officer Leslie Manser, a 50 Squadron pilot flying an Avro Manchester who sacrificed himself so that his crew could abandon the aircraft, was subsequently awarded the Victoria Cross.

The raid proved that the new tactics could be successful; there were few casualties through collisions and subsequently the time over target would be progressively shortened until 700 or 800 aircraft could bomb in less than 20 minutes! The morale of Bomber Command was certainly boosted by this great demonstration of air power and by the wide publicity which followed. That same publicity confirmed Bomber Command's future as a major force. These events also placed Sir Arthur Harris firmly in the public eye, where he would remain for the rest of his life.