Last surviving VC recipient of the Second World War, John Cruickshank, dies aged 105

Header Image: Flight Lieutenant John Cruickshank VC in wartime (left) and in later life (right).

Many readers will have seen that the death of Flight Lieutenant John Cruickshank VC was announced on 16th August. We felt that we should acknowledge his passing and pay our respects. Even in the remarkable annals of the Victoria Cross, the fortitude and endurance shown by John Cruickshank in winning this highest award for valour stand out.

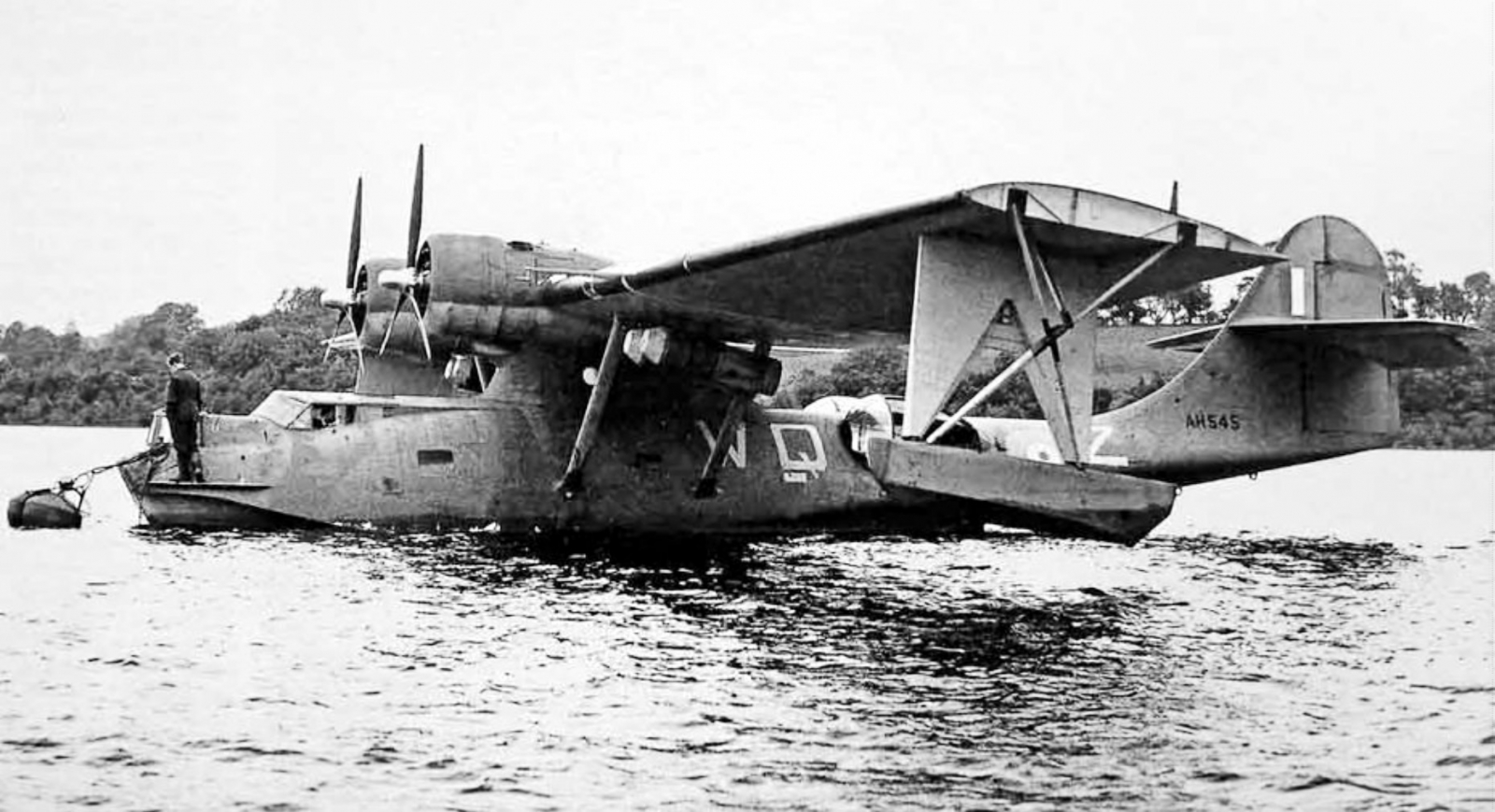

On 17th July 1944, the 24-year-old Cruickshank was the captain of a 210 Squadron Consolidated Catalina flying boat on a 14-hour patrol from Sullom Voe in the Shetland Islands, when he attacked the surfaced U-boat U-361. On the first attack run, at an altitude of 50 feet, the Catalina’s depth charges failed to release and as the aircraft made a second run it was hit by ‘flak’ from the U-Boat. The Catalina’s navigator/bomb-aimer was killed and three other crewmen were injured, including the co-pilot and Cruickshank, who was badly wounded in the chest and legs. With the fuselage holed and on fire, Cruikshank, undaunted, pressed on with the attack, aiming and releasing the depth charges himself. The Catalina crew had the satisfaction of seeing their depth charges straddling the U-boat, which broke up and sank beneath the waves.

The Catalina was badly damaged and its chances of returning to Sullom Voe and executing the necessary water landing, with the large holes in the hull, seemed very poor. Cruickshank meanwhile had 72 wounds, including lacerations to his chest and legs, and shards of shrapnel in his lungs. His crew insisted he leave the co-pilot in charge and carried him out of the cockpit to provide what medical aid they could, although he refused morphine. For the subsequent six and a half hours, slipping in and out of consciousness, he provided advice and instructions to the co-pilot. He then insisted on being moved to the co-pilot’s seat, refusing to allow the aircraft to be brought down until it became light as dawn broke. He then assisted with the water landing and beached the flying boat which would otherwise have sunk.

By that time, he was in a state of complete collapse and had to be taken from the aircraft on a stretcher. On reaching the nearest medical facility he was given a blood transfusion to keep him alive on his journey to hospital, where he was judged by a doctor to be barely an hour from death. He remained on the hospital’s danger list for 10 days. It was two months before he was well enough to receive the Victoria Cross, on 21st September 1944, from King George VI at Holyrood House. Cruickshank’s VC citation said: “By pressing home his second attack in his gravely wounded condition and continuing his exertions on the return journey with his failing strength, he seriously jeopardised his chance of survival. Throughout he set an example of determination, fortitude and devotion to duty in keeping with the highest traditions of the Service.”

Cruickshank never returned to operational flying and left the RAF in 1946 for a career in banking. In March 2004 Cruickshank attended the unveiling by HM Queen Elizabeth II of the first national monument to Coastal Command at Westminster Abbey. In September 2013, the 93-year-old veteran was flown in a Catalina like the one he had once piloted. Cruickshank was a stolid man, loath to romanticise his experience of the war, but apt to deploy his dry sense of humour, once saying, “When I go, I suppose I had better put out the light”. He was the last to die of the 181 people who received the Victoria Cross for their actions in the Second World War.

LEST WE FORGET